Spotlight On Catherine McCurdy – Highlighting the Accomplishments of our Members

feel free to email us [email protected]

-

The Reality of Life: Ob/Gyn Perspectives During COVID-19

Melanie Lucks, , COVID-19, Blog, 0

These are challenging times, but as healthcare workers we are powering through; working in...

-

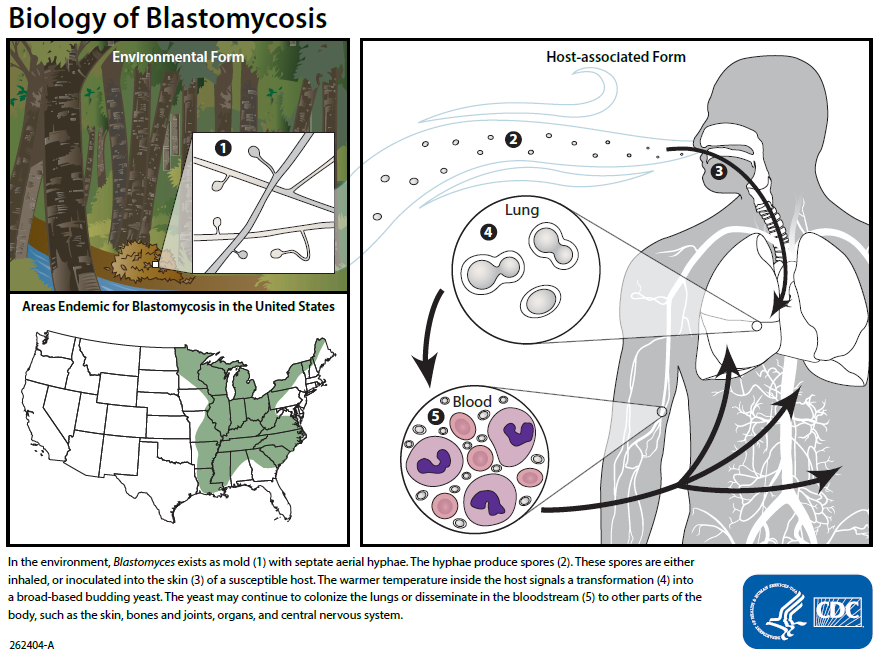

Blastomycosis- Increasing cases reported in Upstate NY

Melanie Lucks, , Blog, 0

"Blastomycosis is an uncommon and under diagnosed disease typically caused by inhalation of Blastomyces spp. fungi, which grow in...

-

Webinar: Sunday Sept 8th, PA Profession in Israel

Melanie Lucks, , Blog, 0

Please join us for our first ever live webinar! Featuring Dr. Oren Berkowitz, PA-C from Ariel University. This event...

-

Adapting Antenatal Care in a Rural LMIC During Covid-19 in Rural Guatemala

Melanie Lucks, , 2020, Blog, 0

Saving Mothers is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to eradicating preventable maternal deaths and birth-related complications in low-resource settings....

-

Emergency Deployments to COVID Endemic Regions

Melanie Lucks, , COVID-19, Opportunities, Blog, 0

Caliburn International Recruiting for immediate deployment to Brooklyn, NY Travel and housing is provided $175/hr + overtime Website for...

-

New Zealand PA Job Opportunities

Melanie Lucks, , Uncategorized, Blog, 0

International Physician Associate Employment Opportunities Rural Family/General Practice-Emergency Department-Urgent Care New Zealand…… North and South Islands Contract: Full time with...

-

Welcome new members from Africa!

Mary Showstark, , Blog, 0

PAGH is happy to announce a new partnership with GACOPA and expanding our membership to PAs/Clinical Officers/Clinical Assistants/Health Officers...

-

Spotlight on International PAs

Jessica Roberts, , Blog, Career Planning and Development, Community, Jobs, Social Network, 0

Series highlighting PAs working around the world. This article is on PA Christopher Casey who works for the U.S....